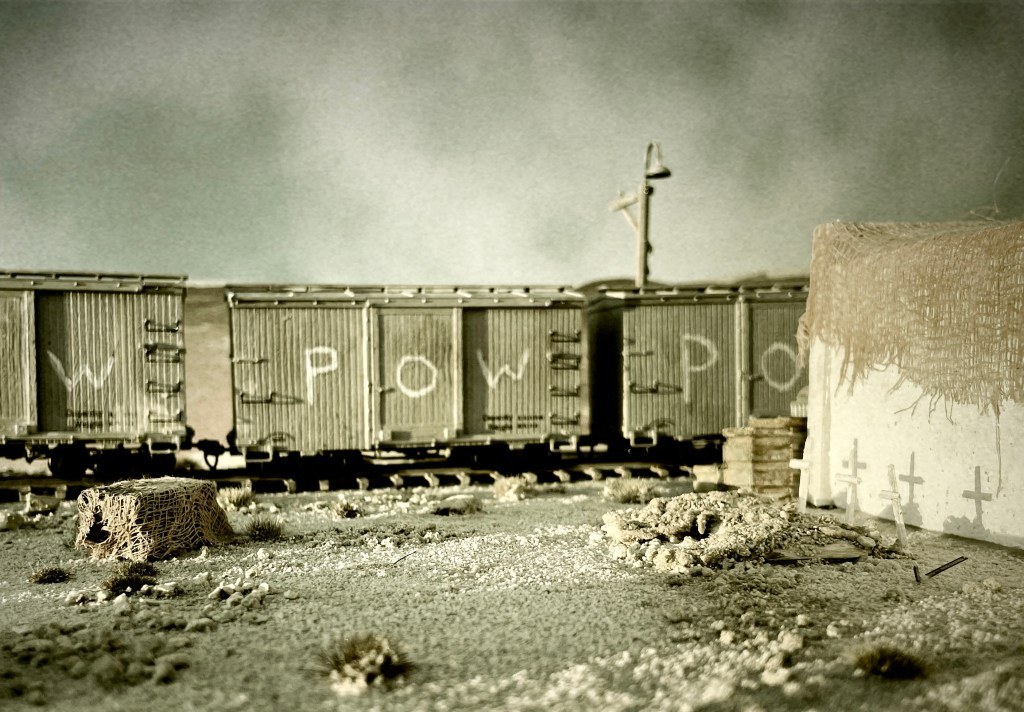

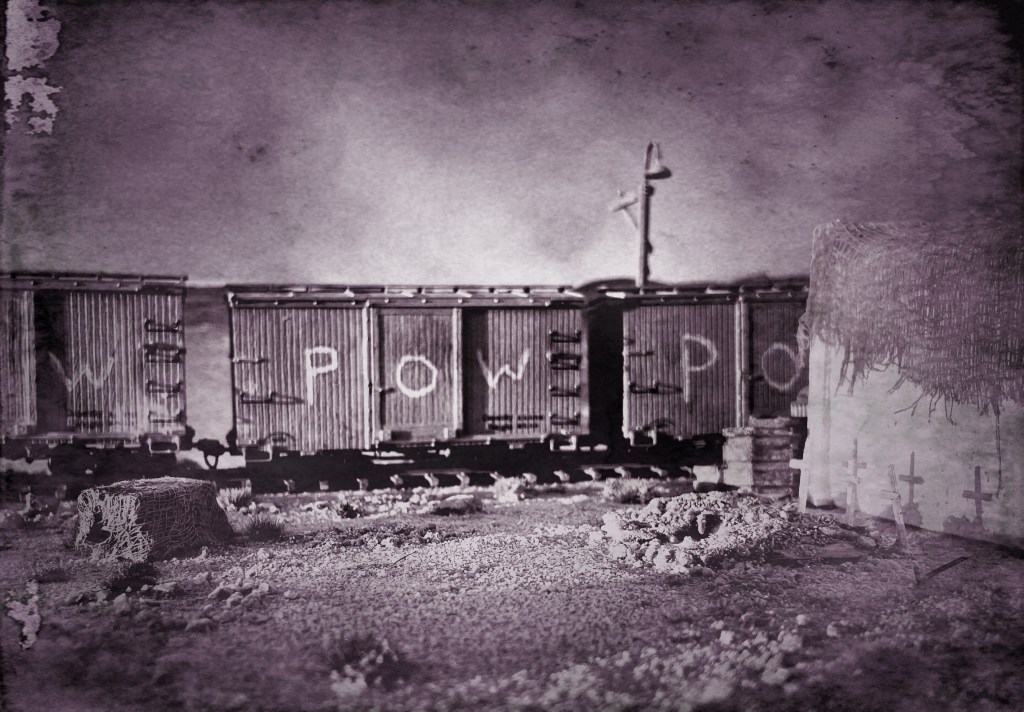

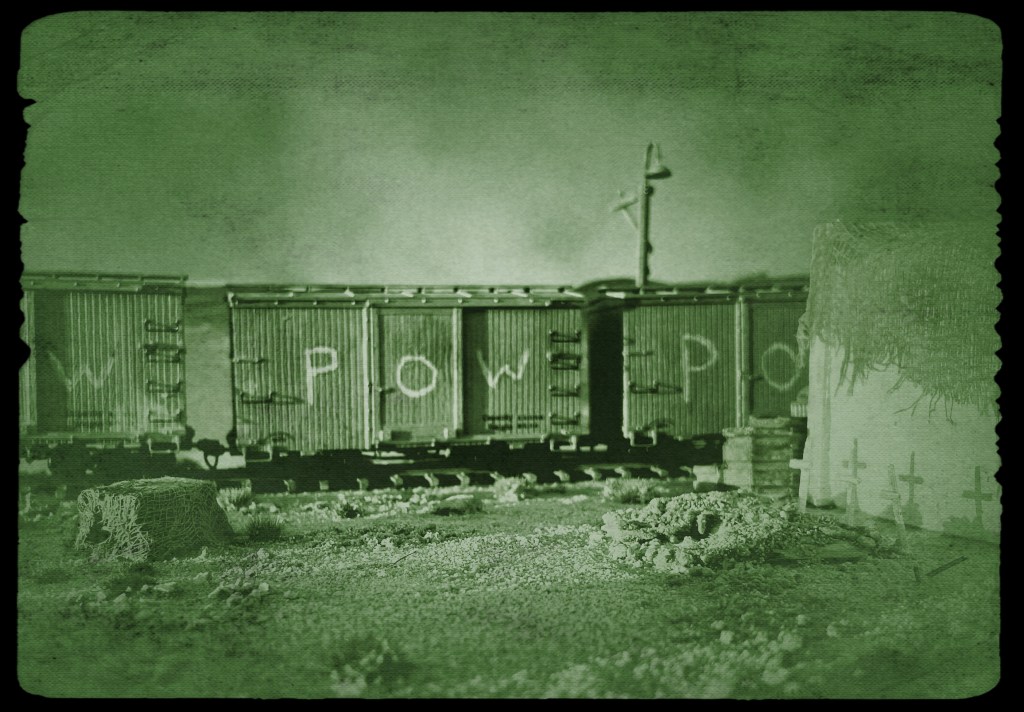

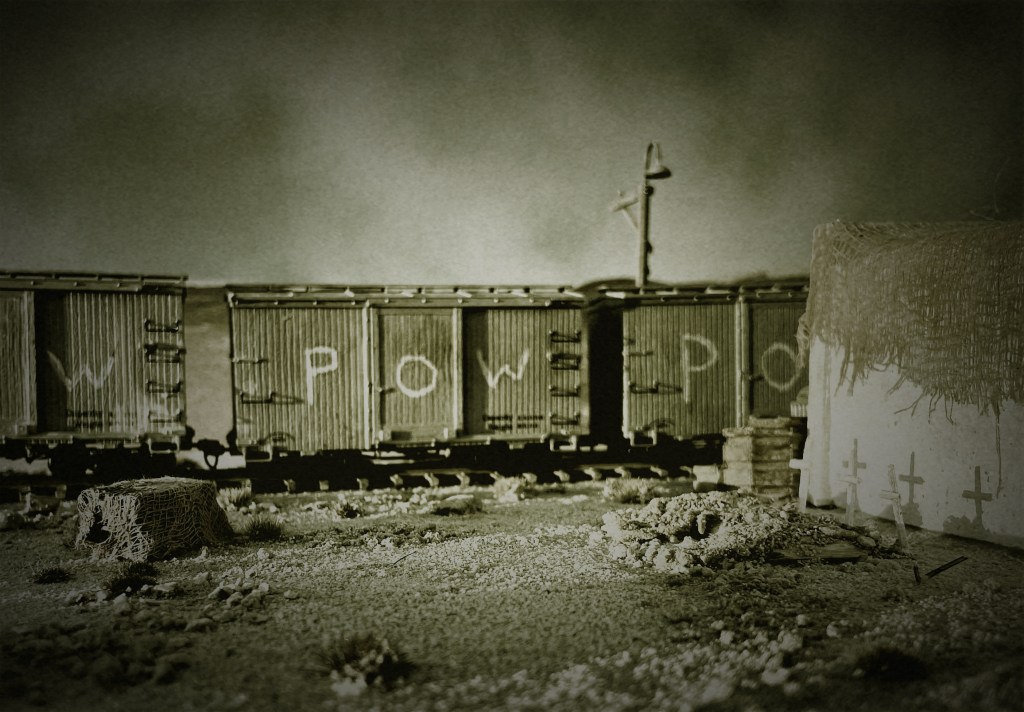

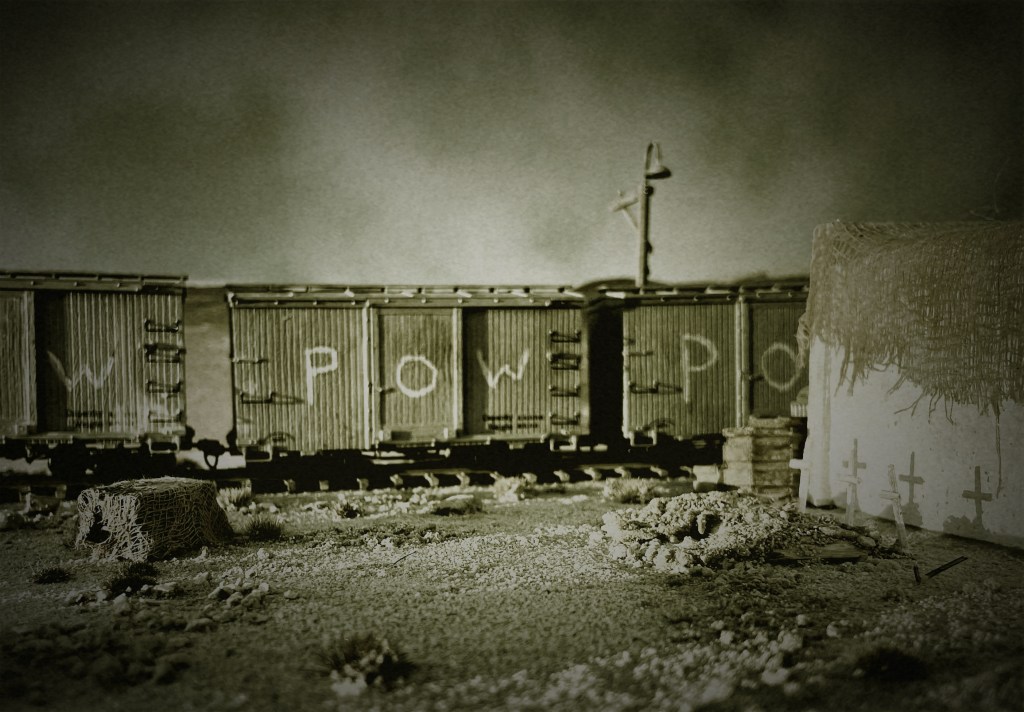

Italian POWs Flood the Railroad

Bibliography with Notes plus Bonus Content

Bierman, John and Colin Smith. War Without Hate. New York: The Penguin Group, 2002, p. 49.

“Tom Bird, a lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade who helped take Tobruk in a letter home: ‘One can’t help feeling that it is a great bit of luck to have been able to have a practice over or two, so to speak, with the Italians. What more delightful people to fight could there be?’”

Cooper, Artemis. Cairo in the War 1939-1945. London: John Murray (Publishers), 2013. Kindle.

Chapter: The Benghazi Handicap

“Back in North Africa, O’Conner cut off the Italians’ escape south of Benghazi at Beda Fomm on 7 February. The exhilarating gallop across the desert, which the men of the Western Desert force had dubbed ‘the Benghazi handicap’, was over. Five days later, on 12 February, General Erwin Rommel arrived in Tripoli.”

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

“These trains were employed to transport Italian prisoners of war, their captured equipment and petrol. The captured Italians, approximately 850 per day, were railed to Barce and petrol was railed back to Benghazi.”

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

pp. 98-99

“The railway men not only faced the danger of aerial attacks but also had to contend with mines laid along the main coastal routes. During an operation at Sollum, where Italian prisoners were being ferried out to the Farida, a mine exploded beneath the Kiwi-crewed vessel. Four crewmen were killed, as were many of the POWs. It seemed German airman cared not that they were probably killing more of their own allies than their enemies had.”

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

p. 176

Chapter 16: WRATH OF THE LUFTWAFFE

“On one tragic occasion the Luftwaffe strafed a train carrying German and Italian prisoners. Approximately 120 POWs were killed and many wounded. Most of the Germans were in locked wagons and could not readily escape the hail of fire directed at them. It was sickening to see men trapped like rats with little hope of escape.”

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

p. 98

Chapter 9: THE RATS OF TOBRUK

“In late January 1940, while en route from Tobruk, the Sollum, ferrying 800 Italian POWs back to Egypt, was strafed by enemy aircraft off the coast at Sidi Barrani. Watching in horror from an escarpment overlooking the beach were railwaymen who saw the terrified Italians rushing for the lifeboats. The boats were soon grossly overloaded and spilled their occupants into the sea, most of whom drowned.

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

Chapter 8: OFFENSIVE AND COUNTER-OFFENSIVE

“The Italians disillusionment was made complete when they later entered Alexandria. They asked their captors what city it was and refused to believe that it was indeed the ancient city founded by Alexander the Great. In keeping with the phenomenal boasting and claims of Mussolini, the ordinary Italian soldier had been told that the ‘courageous’ Reggia Aeronautica had flattened the place out of existence. In fact, the city was totally unscathed.”

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

Chapter 8: OFFENSIVE AND COUNTER-OFFENSIVE

“Elsewhere on the railway network, the transport of prisoners had become a deluge. Just after the beginning of the offensive, the New Zealand railwaymen were running ten trains daily each way between El Dabaa and Mersa Matruh. By 11 December, the ratio of trains altered, with more heading back east rather than westward. Over 130,000 Italian troops were captured in the first few days of Wavell ‘s offensive, many of them simply surrendering to the Australian and British troops en masse even though they often outnumbered their attackers. No accurate tally was ever recorded as to how many POWs were transported by rail from Mersa Matruh and Hatawa, but it was a high proportion of the 130,000 captured. This unexpected situation caused more logistical problems for the Allies: these prisoners had to be guarded, fed and transported back to Egypt, putting further strain on already stretched resources. Using any available carriages, the railwaymen were charged with removing captured Italian soldiers from the front line.”

Chapter 34 plus Bonus

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

Chapter 14: HOW THE RAILWAY WAS OPERATED

“It became preferable to allow some trains full of troops to pass by without stopping. If these trains were given permission to enter a station, several hundred men would detrain and make use of the opportunity for a ‘comfort stop’. The blockman, quite naturally, had reservations about so many men using his surrounds as a toilet – the fly problem was bad enough without exacerbating the situation. Therefore, he would hold these trains outside the station and the troops could then foul the desert well away from the blockman’s quarters.”

Chapter 34 Plus Bonus

Latimer, Jon. Operation Compass. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2000. Kindle.

Chapter: Opposing Forces

“The Italian Army’s gross deficiencies were not limited to transport and armour; there were not enough anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns. Added to the inadequacies of their intelligence service, which vastly overestimated British strength throughout the campaign, the subsequent reputation of the Italian as a fighting soldier appears unfair. It has overlooked the handicap he fought under, and ignored the gallantry displayed, especially by the artillery who often fought until shot down around their guns. After all, it takes greater courage to go into battle with bad equipment and inept doctrine, than full confidence in one’s military institutions.”

Moorehead, Alan. The Desert War: The Classic Trilogy on the North African Campaign 1940-1943. London: Aurum Press Ltd, 2013. Kindle.

BOOK ONE—The Mediterranean Front: The Year of Wavell 1940-41: Nineteen

“Something like a quarter of a million Italian soldiers were safe in concentration camps in Egypt, India and South Africa.”

Moorehead, Alan. The Desert War: The Classic Trilogy on the North African Campaign 1940-1943. London: Aurum Press Ltd, 2013. Kindle.

BOOK ONE—The Mediterranean Front: The Year of Wavell 1940-41: Eleven

“…the mere occupation of Benghazi would not mean the destruction of the still very strong forces which Graziani had under his command. These would simply escape down the coastal road toward Tripoli to fight another day…an attempt should be made to cut them off. This would involve a forced march of some two hundred miles across an open desert that was largely unmapped, in circumstances so unfavourable as to be almost prohibitive.”

Rainier RE, Major Peter. Pipeline to Battle: An Engineer’s Adventures with the British Eighth Army. Auckland: Pickle Partners Publishing, 2013. Kindle.

Chapter 13: VICTORY

“For days afterwards long trainloads of Italian prisoners streamed eastward to Alexandria along the Western Desert Railway. Graziani, so the prisoners told us, had been on the even of another advance toward the Nile Delta. A day or two before our attack he had harangued his troops and promised that they would be drinking Nile water before the year was out. He was a true prophet. They drank Nile water before Christmas…‘waters of Babylon’—the water of captivity”

Shores, Christopher F., and Giovanni Massimello with Russel Guest. A History of the Mediterranean Air War, 1940-1945: Volume One: North Africa. London: Grub Street, 2012. Kindle.

CHAPTER 5 ENTER THE LUFTWAFFE

“In just two months this small force had utterly defeated an army more than four times its size, mainly due to brilliant leadership, real mobility, and great coordination between land, air and naval forces. 130,000 prisoners had been taken, with 1,300 guns and 400 tanks captured or destroyed.”

Wahlert, Glenn. The Western Desert Campaign 1940-1941

(Australian Army Campaigns Series Book 2). Sydney: Big Sky Publishing, 2011. Kindle.

Chapter: Aftermath

“…advanced over 800 kilometres…had captured more than 130,000 prisoners…400 tanks, thousands of transport vehicles and a couple of army brothels.”

Wahlert, Glenn. The Western Desert Campaign 1940-1941

(Australian Army Campaigns Series Book 2). Sydney: Big Sky Publishing, 2011. Kindle.

Chapter: Tobruk Seized

“On the same night, Italian SM.79 bombers looking for targets around Tobruk saw the numerous fires that had been lit by Italian prisoners of war and bombed them. Hundreds of Italian prisoners were killed or injured.”

Wahlert, Glenn. The Western Desert Campaign 1940-1941

(Australian Army Campaigns Series Book 2). Sydney: Big Sky Publishing, 2011. Kindle.

Chapter: Opening Moves

“In contrast to popular belief, in many locations the Italians fought bravely. Their artillery was particularly aggressive and accurate, often continuing to fire until all the crew were killed. However their positions were poorly sited, their men inadequately trained or equipped, and their officers generally failed to inspire and lead from the front.”

Whiting, Charles, Disaster at Kasserine: Ike and the 1st (US) Army in North Africa 1943. Pen and Sword Military, First Edition, 2003.

“…Breakfast over, men would be seen striding purposefully into the countryside, ‘Army Form Blank” in one hand, spade in another. They were ’taking a shovel for a walk’ as they called it…”

Bonus Illustrations