Logistics: The Desert Railroad

Bibliography with Notes plus Bonus Content

Bickers, Richard Townshend. The Desert Air war: a gripping historical account of the RAF’s role in North Africa during World War II. UK: Lume Books, 2018. Kindle.

Chapter One

“At Mersa Matruh, with its fig trees, white domes and minarets, once stood Cleopatra’s summer palace where she entertained Anthony. Between the two world wars it had become a popular watering place for rich Cairene [from Cairo] families.”

Jackson, W.G.F. The Battle for North Africa 1940-43. New York: Mason/Charter Publishers, 1975. (page 38)

“…there are four important topographical features: the sandy coastal strip; the easily crossed pebble and boulder strewn Libyan plateau; the difficult salt marshes of the Qattara Depression and sand dunes of the Libyan sand sea; and escarpments which divide the coastal strip from the desert plateau…Mersa Matruh where Antony and Cleopatra enjoyed each other and where O’Conner had his advanced logistic installations…

On the British side, a railway, water pipe-line and tarmac road reached as far west as Mersa Matruh.”

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

Chapter 13 THE DESERT RAILWAY CONTINUES

“A large marshalling yard was constructed at Charing Cross as a staging post for trains that would eventually travel westward. This was the result of an initiative by Colonel Anderson. Rather than build conventional railyards with loop sidings and shunting roads all parallel to the main line, Anderson chose to build a large balloon type of yard with service spurs branching off at varying distances. The three major commodities serviced by these spurs were petrol, oil and lubrication, hence they became known as ‘POL’ sidings. Other spur lines were specifically designed for rapid unloading of armoured vehicles…Such a widely dispersed yard made it a far more difficult target for aerial bombardment. As there was no lack of space in the desert, Anderson’s design was adopted for farther major railway yards with some yards having up to nine miles of service tracks.

“While both companies were employed on constructing the line, it was generally decided that as one company worked on the extension, the other would then lay out marshalling yards and build accessories to the yards.

“…If motor transport had been the only means possible, consumption of rubber, fuel and manpower would have been enormous. …Having the railway to bring the tanks all the way from Suez in less than 24 hours saved the British hundreds of tank transporters and the tanks themselves from desert-induced wear and tear,” p. 144.

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

Chapter 5 EL DABAA AND MERSA MATRUH

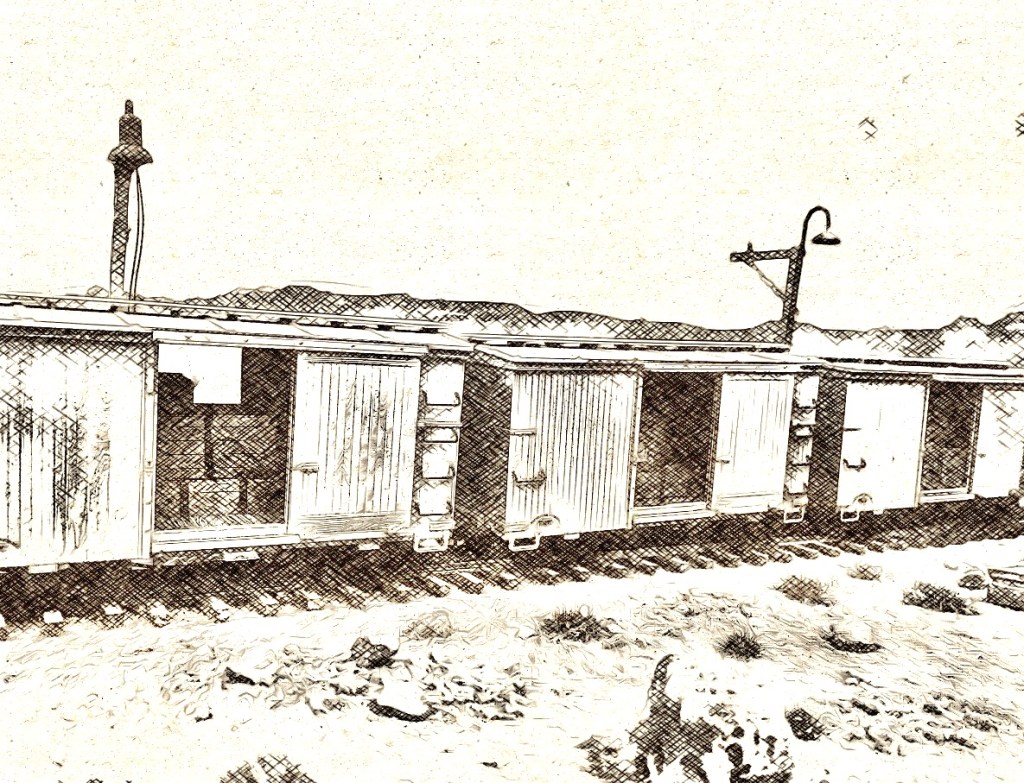

“…a detachment of operating personnel was sent to Mersa Matruh, the western Desert Railway terminus. Situated as it is right on the coast, Mersa Matruh was a popular holiday destination for the wealthy from Cairo and Alexandria.

“Anti-aircraft batteries manned by Egyptian soldiers went into action at Mersa Matruh in the first weeks of the war…

“The town was an important target and the New Zealanders were frequently obliged to take cover as enemy planes roared overhead dropping bombs on them,” p. 67.

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

Chapter 5 EL DABAA AND MERSA MATRUH

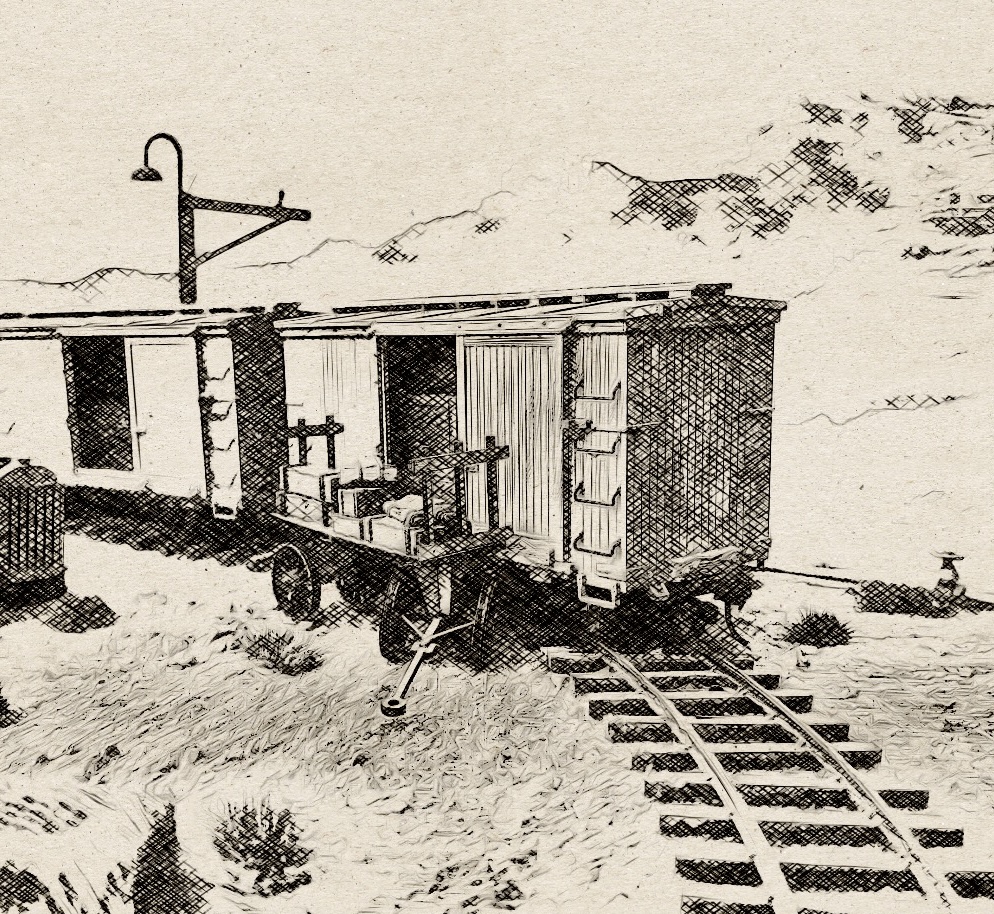

“The long military sidings that serviced the depots and the marshaling yards were recent additions to El Dabaa station. The new military sidings were constructed at the request of the British government for the purpose of the desert campaign. The sidings enabled wagons delivering war materials to be delivered right into the depots from the main line, thus avoiding the transhipment to motor transport. To the west of the station there were several other ‘roads’ (railway parlance for railway tracks) meandering away in different directions serving petrol dumps, Royal Engineers’ stores, armored vehicles’ loading ramps, ordnance, RASC (Royal Army Service Corps) and NAAFI [Navy, Army, Airforce Institutes] depots and a field bakery. One long siding led away into the far distance east of the station and, space at intervals towards its extremity where it curved toward the Mediterranean, were several large ammunition and bomb dumps indifferently camouflaged against enemy observation,” pp. 62-63.

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

Chapter 16 THE WRATH OF THE LUFTWAFFE

“The threat of aerial attacks created a tense atmosphere whenever train crews ventured out onto the main line. The drone of bombers, the unnerving swiftness of low-level fighters and even the terrifying scream of the occasional Stuka dive-bomber attacks, soon became routine for the railwaymen. When the Germans intervened in the North African Campaign to assist their erstwhile Italian comrades, attacks on trains out in the open became increasingly effective. The German aviators had had experience in close support operations during the Spanish Civil War and they put their experience to lethal effect in this theatre. Low-level strafing was a specialty of many of the Luftwaffe pilots who served in North Africa,” p. 171.

Moorehead, Alan. The Desert War: The Classic Trilogy on the North African Campaign 1940-1943. London: Aurum Press Ltd, 2013. Kindle.

BOOK TWO—A Year of Battle: The Year of Auchinleck 1941-42: Eleven: May in Gazala

“…Certainly the Germans and the Italians had all the advantages. Whereas they could bring a tank into the desert within one month of leaving its workshop in Europe. It took the British three months or more to get the same vehicle across from England or America.”

Shores, Christopher F., and Giovanni Massimello with Russel Guest. A History of the Mediterranean Air War, 1940-1945: Volume One: North Africa. London: Grub Street, 2012. Kindle.

Chapter 2 The Opening Rounds

“The obvious advantage enjoyed by the Regia Aeronautica in Cyrenaica was the ability to receive reinforcements rapidly both from Tripolitania, and from units based in Sicily and Italy, capable of flying directly across the Mediterranean.”

Wahlert, Glenn. The Western Desert Campaign 1940-1941

(Australian Army Campaigns Series Book 2). Sydney: Big Sky Publishing, 2011. Kindle.

Chapter: The Leaders

“By the time Mussolini declared war in June 1940, Wavell had already laid the foundation for an eventual British victory in the Middle East. He achieved this through the establishment of an effective logistics support organisation and infra-structure which included ammunition and fuel depots, subsidiary refineries, water pipelines and railways…”

Bonus Illustrations