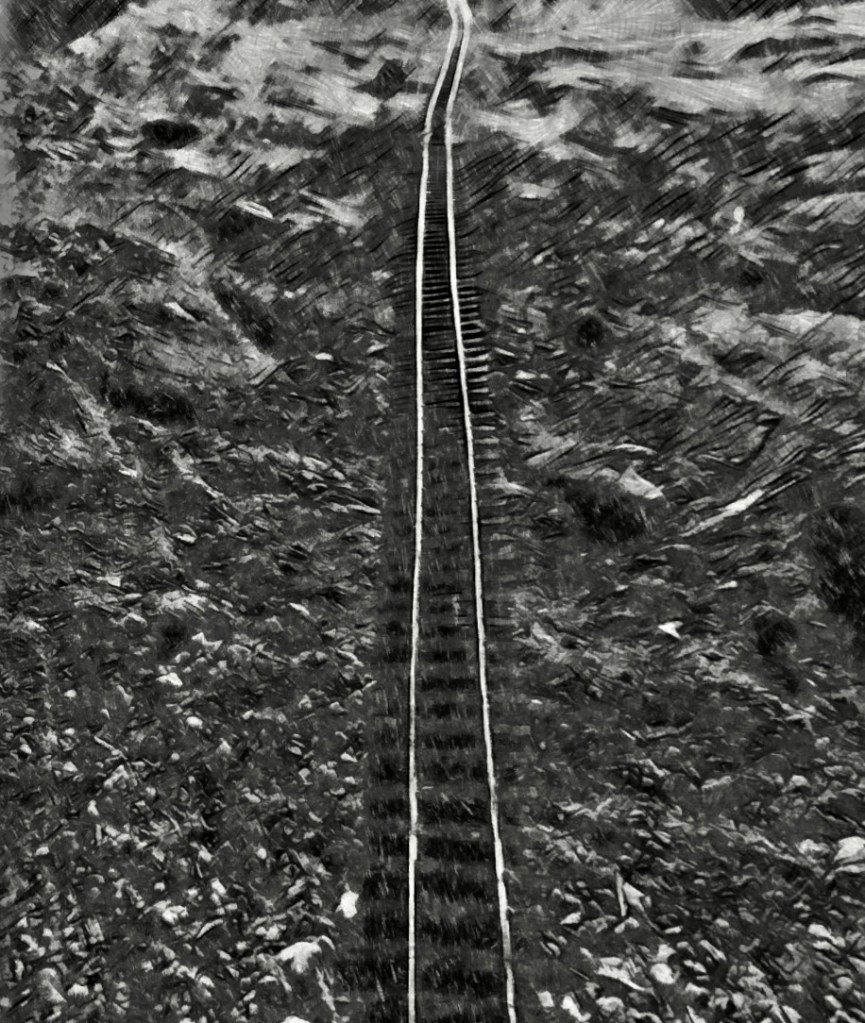

Silver Rails in the Moonlight

Bibliography with Notes plus Bonus Content

Braddock, David. Britain’s Desert War in Egypt and Libya, 1940-1942: ‘The End of the Beginning’. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books, 2019. Kindle.

Chapter 7 The Replacement of Wavell and the Preparation for “Crusader”

“ ‘Crusader’ was a nightmare for the administrative staff of the 8th Army, who were faced with the task of arranging for the supply of the army as it advanced 210 miles beyond its railhead and fought a battle of manoeurvre i(sic) in a roadless and waterless region.

“Huge stocks of fuel, ammunition and water had to be established within easy reach of the fighting and this alone required an extension of the railhead…ordered this to be begun in May, but ‘Battleaxe’, in particular, had delayed progress and it was September before serious work was resumed. Thereafter two companies of New Zealand railway troops laid two miles of track each day…”

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

“In 1940, as a result of Britain’s request to New Zealand for help with the North African Campaign, the New Zealand Government called on the country’s railwaymen as volunteers to construct and operate a railway network in the Western Desert. This was seen as absolutely necessary to supply the bulk of the Eighth Army’s requirements to an ever-shifting front line in the event of a major offensive. Over 1300 men answered the call and, with a minimum of military preparation, were soon on their way. Thus began an adventure that culminated in the Battle of Alamein, during which Field Marshal Mongomery stated, ‘Well, it’s now the railway versus Rommel.’ In his memoirs, Rommel says that ‘the greatest advantage the Eighth Army had over the Afrika Korps was the desert railway’.”

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

A Report from a New Zealand War Correspondent published in the New Zealand Herald, 1942, pp. 13-14.

“NEW ZEALAND RAILWAYMEN CARRY ON DURING HEIGHT OF BATTLE,” p. 13.

“During the most severe air attacks one train took seven hours to go 53 miles. Six times the train stopped while the crew jumped clear to avoid machine gun fire,” p. 14.

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

A Report from a New Zealand War Correspondent published in the New Zealand Herald, 1942, pp. 13-14.

“In October 1940 they [New Zealand railroad workers] went to the desert to handle the increased traffic on the western end of the Egyptian State Railways system,” p. 14.

Judd, Brandon. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Publishing Press, 2003. https://www.nzsappers.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Desert-Railway.pdf

Chapter 16 WRATH OF THE LUFTWAFFE

“Maintaining blackout conditions was a priority for the railwaymen in order to hamper these nightly raiders. During the desert campaign, railwaymen were somewhat unnerved to learn from RAF pilots that the railway track stood out in stark contrast to the surrounding desert during clear moonlit nights. To the airmen, the rails resembled silver ribbons in contrast to the blackness of the ground, and wherever the rails were darkened a train was traversing this section. All the airmen had to do was to line their guns up with the shadow and fire. To eliminate the risk of a pilot spotting the flash of light coming from the firebox whenever the fireman opened the doors to stoke the fire a tarpaulin was stretched between the tender and locomotive. This certainly reduced the risk but created a hot and claustrophobic atmosphere in which to work.” (page 170)

Moorehead, Alan. The Desert War: The Classic Trilogy on the North African Campaign 1940-1943. London: Aurum Press Ltd, 2013. Kindle.

BOOK ONE—The Mediterranean Front: The Year of Wavell 1940-41: One

“This road, some three hundred miles in length, had a relatively good macadam surface, especially the Cairo-Alexandria section, and running parallel to it beyond Alexandria was a single-track railway…

“…To Mersa Matruh went Antony and Cleopatra to enjoy that glorious bathing.”

Rainier RE, Major Peter. Pipeline to Battle: An Engineer’s Adventures with the British Eighth Army. Auckland: Pickles Partners Publishing, 2013. Kindle.

PART ONE Chapter 7: Surgeons of Bombs

“But bombing a railway line in the open desert is wasted effort as far as serious interruption of traffic is concerned. In mountain country the bombing of a bridge or a high embankment may tie up a railway for days, but in that flat, monotonous desert its maximum damage is a few splintered ties and a broken pair of rails, reparable almost within the hour.”

Rainier RE, Major Peter. Pipeline to Battle: An Engineer’s Adventures with the British Eighth Army. Auckland: Pickles Partners Publishing, 2013. Kindle.

PART ONE Chapter 2: Joining the Sappers

“…unless of course you’ve had railway experience. We’re forming a railway company and have vacancies for an officer or two…

“I once built a railway.”

Bonus Illustrations