Italy’s Savoi-Marchetta SM.79 Sparviero (Sparrow Hawk)

Bibliography with Notes plus Bonus Content

Cooper, Artemis. Cairo in the War 1939-1945. London: John Murray (Publishers), 2013. Kindle.

Chapter: The Benghazi Handicap

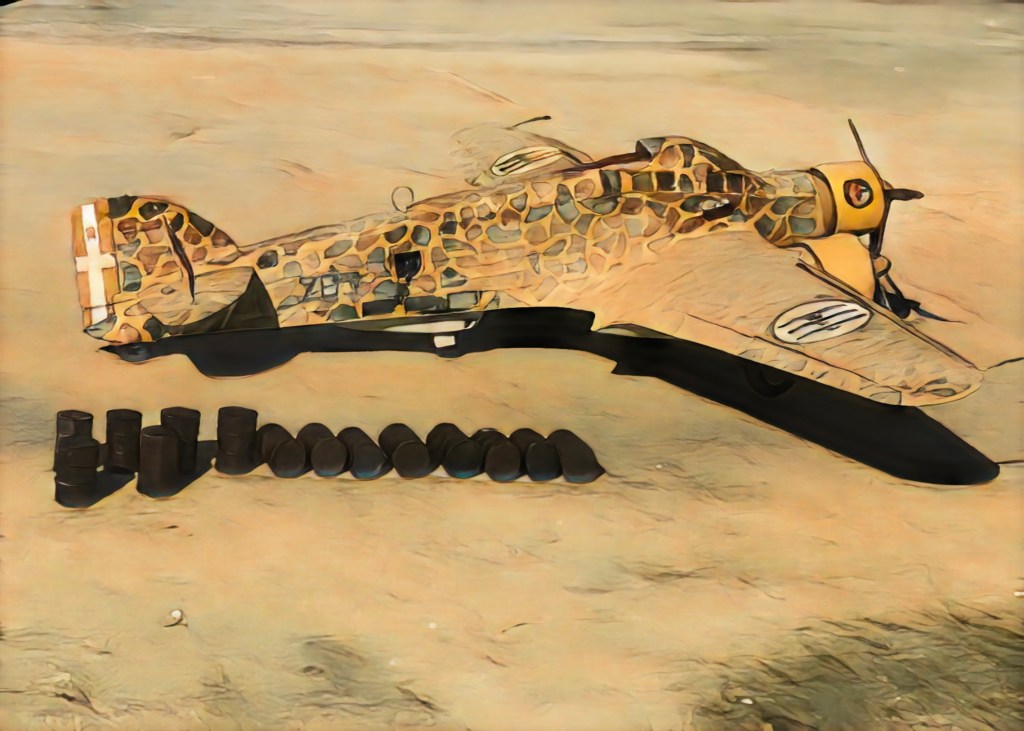

“…to demonstrate its effectiveness and reassure the local population, a captured Italian plane was exhibited in Alexandria. The idea was that the spectators would be filled with admiration for its British captors; but, in their eyes, the aircraft only confirmed the power of the Italian Empire.”

Cooper, Artemis. Cairo in the War 1939-1945. London: John Murray (Publishers), 2013. Kindle.

“…transferred to Libya to support the advance on Sidi Barrani, from Derna up to September 18. Close support sorties and bombing of Egyptian targets were carried out for the rest of the year.”

Cooper, Artemis. Cairo in the War 1939-1945. London: John Murray (Publishers), 2013. Kindle.

“The unit was nearly always understrength because of lack of spares and the use of an aircraft not designed for the ground support role.”

Dunning, Chris. Courage Alone—The Italian Airforce 1940-1943. Manchester: Crecy Publishing Limited, 2010. (page 247)

“…the Germans sent their torpedo crews for training in Italy, for future use against both Mediterranean convoys and Arctic convoys. The Germans also used the the potent Italian Whitehead (Fiume) torpedoes as standard. Thus even Luftwaffe torpedo successes in the Mediterranean could be attributed to Italian equipment.”

“The first experimental unit (for torpedo attack by air) was formed in August 1940” (by the Italians and eventually two entire units)…were converted from level bombing to torpedo bombing and put into action with very little training.”

“The main aircraft used were the SM 79 and SM 84, both equipped to carry two torpedos, although it was found to be more efficient to carry just one, fitted slightly off-centre under the fuselage.”

“The crews did not like the SM 84 mainly due to its weak engines, and most units eventually re-equipped with ‘Il Gobbo’ (‘the Humpback’), as the reliable SM 79 was nicknamed.”

Dwyer, Larry. The Aviation History Online Museum. Savoia-Marchetti SM.79. http://www.aviation-history.com/savoia-marchetti/sm79.html

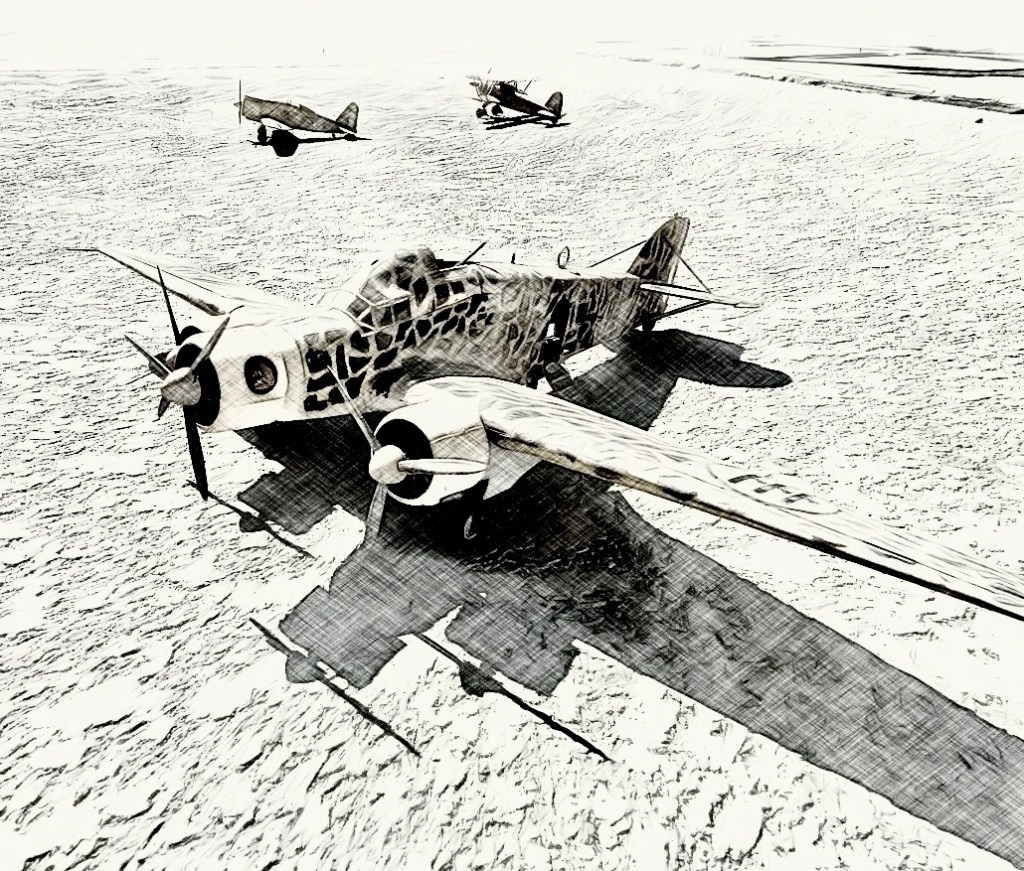

“The SM.79 first saw combat during the Spanish Civil War; in this theatre, it operated without fighter escorts, normally relying on its relatively high speed to evade interception instead. “

HandWiki. Engineering: Savoia-Marchetti 79. https://handwiki.org/wiki/Engineering:Savoia-Marchetti_SM.79

“Its wooden structure was light enough to allow it to stay afloat for up to half an hour in case of water landing, giving the crew ample time to escape…”

HandWiki. Engineering: Savoia-Marchetti 79. https://handwiki.org/wiki/Engineering:Savoia-Marchetti_SM.79

“It had originally been conceived as a fast monoplane transport aircraft, capable of accommodating up to eight passengers and of being used in air racing…”

Shores, Christopher F., and Giovanni Massimello with Russel Guest. A History of the Mediterranean Air War, 1940-1945: Volume One: North Africa. London: Grub Street, 2012. Kindle.

Chapter 2 The Opening Rounds

“Following nightfall, the first mission was undertaken by five Italian S.79 torpedo bombers…”

Shores, Christopher F., and Giovanni Massimello with Russel Guest. A History of the Mediterranean Air War, 1940-1945: Volume One: North Africa. London: Grub Street, 2012. Kindle.

Chapter 2 The Opening Rounds

“One of the S.79s shot down…on 17 August 1940 crash-landed…and his crew surviving to become PoWs…the aircraft was recovered and subsequently put on display in Alexandria.”

Shores, Christopher F., and Giovanni Massimello with Russel Guest. A History of the Mediterranean Air War, 1940-1945: Volume One: North Africa. London: Grub Street, 2012. Kindle.

Chapter 6 Reverses and Reinforcements

“Of the second aircraft, which had departed at 1725…there was no news. Subsequently, many years later in 1960, its wreck was found…by an oil company exploration team. The remains of the five crew members were found nearby, whilst the body of the sixth, the gunner…were discovered about 55 miles away…”

Shores, Christopher F., and Giovanni Massimello with Russel Guest. A History of the Mediterranean Air War, 1940-1945: Volume One: North Africa. London: Grub Street, 2012. Kindle.

Chapter 6 Reverses and Reinforcements

“…Needless to say with the arrival of the Luftwaffe in Greece and Sicily, the Mediterranean fleet got some awful shocks and despite the shocks of Taranto and Matapan the Luftwaffe closed the Gibralter-Suez route for two whole years from 21 May 1941 until may 1943.”

Wahlert, Glenn. The Western Desert Campaign 1940-1941

(Australian Army Campaigns Series Book 2). Sydney: Big Sky Publishing, 2011. Kindle.

Chapter: Weapons List

“Originally developed by the Italian aeronautical industry in the mid-1930s to provide fast postal links to the African colonies, this aircraft was converted to military use in the late 1930s, with the military version officially named Sparviero (‘sparrow hawk’). However, its crews soon nicknamed it Gobbo Meladetto (‘damed hunchback’) due to the distinctive hump on the upper forward fuselage that housed the forward and dorsal gunner’s positions. It quickly gained a reputation as an elegant aircraft capable of record-breaking runs. The Sparviero was first employed as a bomber in Spain in the late 1930s where it was considered a great success…Renowned for its precision bombing ability, it was also employed in the Mediterranean theatre as a successful torpedo bomber where it was very active against British shipping.”

Bonus Illustrations